Science in Story: Craft techniques for fiction writers

Andrea Baldwin

Scientists seek to tell meaningful, logical, comprehensive stories that explain how the world works. Allowing for differences in cultural logic, storytellers have long sought to do the same. Scientists and storytellers may use different methods and tools in their explorations, communicate using different discursive modes, and value different outcomes, but at heart they are on the same quest: to make sense of things.

As a writer of eco-fiction, I want the deepening of knowledge about the natural world to be part of the joy, fascination and value of every story. Information accumulates through the methodologies of various sciences – astronomy, geology, biology, oceanography, physics – but can only influence cultural and political decision-making if widely known and understood. It’s bemusing and frustrating, therefore, when a reader says they ‘skipped the description’ of the rock-pool, meteor shower, laying turtle or flowering eucalypt I wanted them to encounter and appreciate at a more profound, connected level. They tell me they are keen to get back to the story, meaning the emotional and behavioural interactions among characters.

How can a writer entice a reader to experience the other-than-human world as more than mere backdrop for the antics of humans? How do we blend science and story?

Expository information within a story always requires skilful handling in terms of length, language and placement. Creative writing courses recommend drip-feeding information, or presenting it subtly during moments of emotional action, to avoid holding up the story’s momentum or jolting the reader out of its emotional reality. Even greater care is required where the information risks being experienced as an incursion from the ‘real world’ where the reader lives, into the fictional world where the characters live. There are techniques available to manage this risk, which vary according to genre: for example science fiction, crime fiction and horror are generally more forgiving of technical description explanations and the citing of statistics than literary fiction, romance or fantasy.

What a bite of scientific information means to the characters, and what it motivates within the story, are key to ensuring that such content never appears decorative or extraneous, but rather helps drive the story’s conflicts. Narrative conflicts are widely categorised into intrapersonal/internal, interpersonal/between characters, societal, technological, supernatural/divine, or conflict between the character and nature itself. Information that reads as ‘sciencey’ therefore needs to pose a threat or offer a promise: it must make characters fear or want something, causing them to think, feel and do things they wouldn’t have done without the information. A few techniques are briefly outlined below, with exemplars drawn from contemporary literature.

The techniques briefly outlined below can be observed in many novels.

Text within a text: characters can may access receive scientific information through a letter, email, report, article or book, either fictional or quoted from outside the world of the novel. The character may have been sent the document, discovered it through research or encountered it by accident. It may be a text familiar to the character but new to the reader. Or it may be a text the character is writing, sharing knowledge with the reader while formulating it for themselves. Referring back to a central text throughout the story is an established structural device: for example Richard Flanagan’s picaresque novel Gould’s Book of Fish is structured around a surreal fictional version of convict naturalist painter William Gould's Sketchbook of Fishes.

Speech and dialogue: a speech or presentation within the story can justify the sharing of scientific information, so long as the reader is invested in the stakes (e.g. will this presentation make or break the character’s career?) Conveying science through dialogue can work well when the information itself demands urgent action, or when the way it is shared reveals to the reader what is happening emotionally between characters. When Rachel explains facts about wolf biology to other characters in Sarah Hall’s The Wolf Border, these facts always resonate with implications about Rachel’s past and future.

Internal monologue: a character may muse on scientific observations or information, pondering ways in which this information relates to or represents important aspects of their life, personality and world, people they love, decisions they need to make. In Donna Mazza’s Fauna, the hours Stacey spends introducing the ecosystems of coast and estuary to Asta inscribe for the reader both the bond and the distance between mother and daughter.

Repetition: returning again and again to a scientific observation or concept, with each revisit uncovering different dimensions or posing contradictions, can draw the reader in. Sarah Kanake uses this technique in Sing Fox To Me, where the reiterated possibility of Tasmanian tigers still existing takes the reader ever farther into the contrasting characters of Clancy Fox and each of his two grandsons.

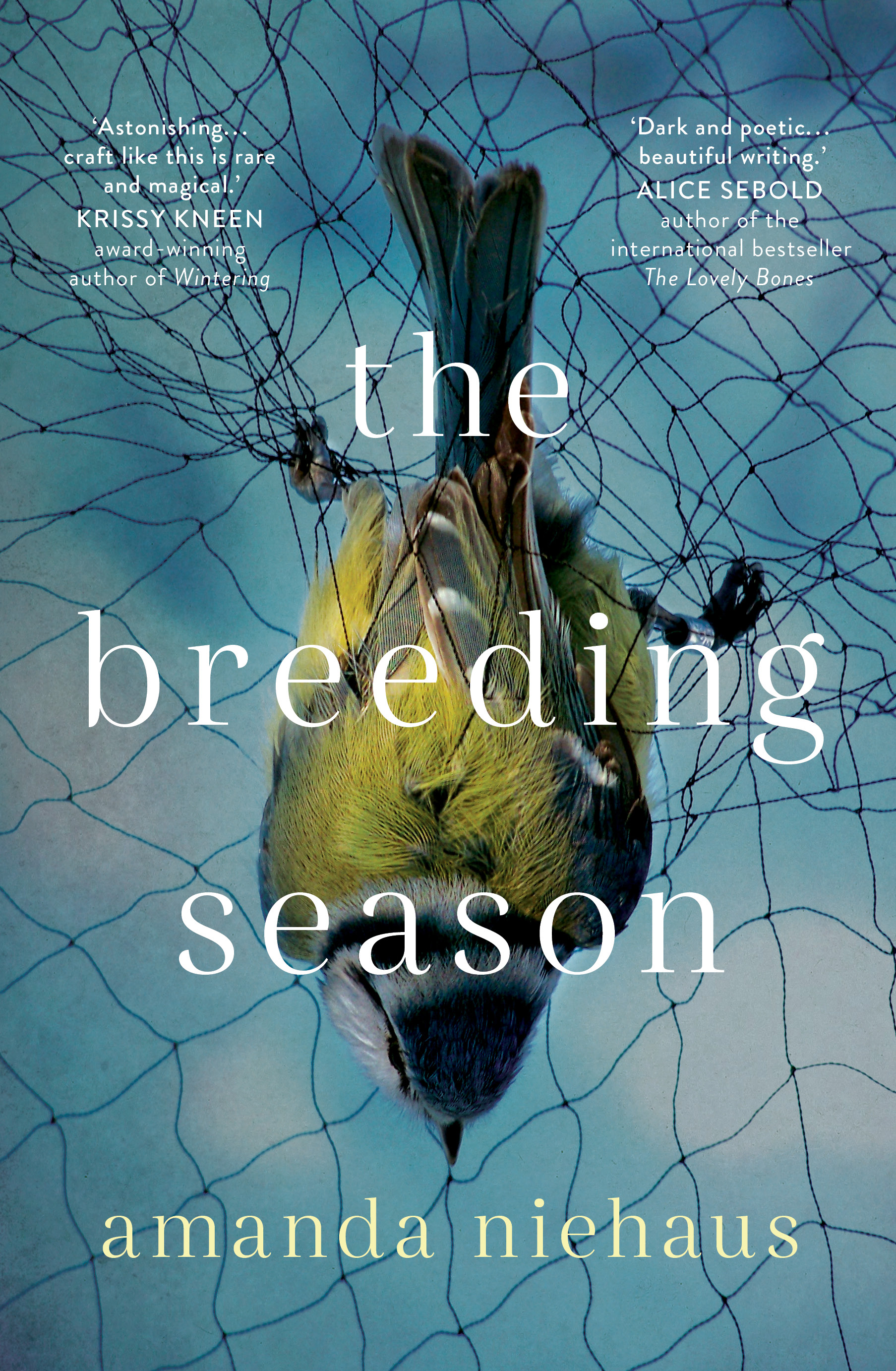

Symbol: if characters themselves symbolise humans in the ‘real world’, an extra circuit of symbolism is added when these characters reflect on how processes in the other-than-human world may symbolise aspects of the human condition, society and relationships. In Amanda Niehaus’s The Breeding Season, for example, Elise and Dan negotiate complexities of love, sex and grief partly through sharing life-cycle knowledge about other species: koalas, bonobos, mosquitofish.

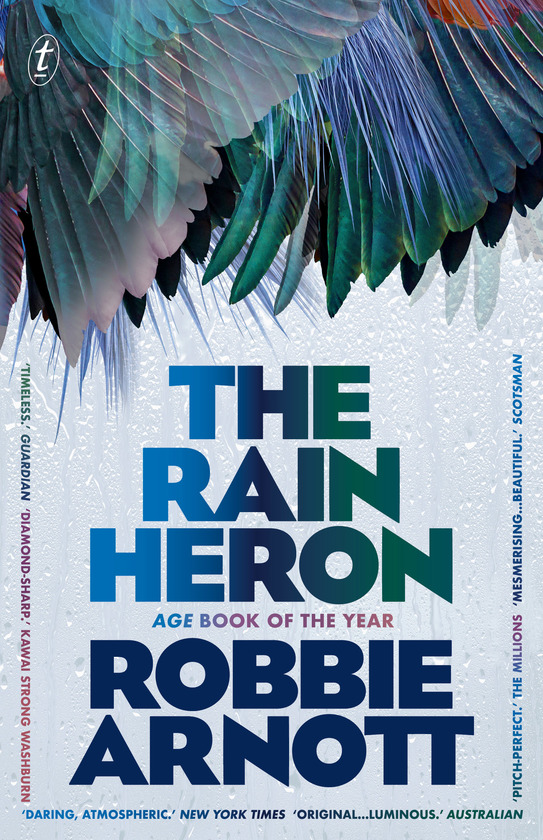

Myth: blending fact and fable, enticing the reader to meet the other-than-human natural world through a powerful sense of the mythic, is a traditional storytelling technique that has produced striking recent works of literary fiction. Robbie Arnott’s The Rain Heron is often described as an eco-fable about the fragility of human relationships with the planet and with one another.

In the end, classifying writing techniques is at least as problematic as taxonomising species. But the above list provides a sample of ways that writers may inflect their prose with science, engaging readers in meaningful interaction with the natural world through information interwoven with character, action and emotion.

Feature image via JSTOR