A Transect of the Science-Poetry Incline

Carol Jenkins

When I left my job in the then National Industrial Chemical Notification and Assessment Scheme, that went by the rhyming and trivialising acronym NICNAS, at the usual departure afternoon tea, the Director — who knew I was writing a novel — said, with that curious inflection of half-worry half-anticipation, that she hoped I wouldn’t be writing about NICNAS. I had one of those eye-rolling ‘in your dreams’ kind of reactions. The novel I was working on was a coming of age love-migration story. I didn’t think of it as having any science content. But it did. Mary, the main character, is obsessed with collecting and identifying moss, she draws her specimens and is desperate to get a microscope. To me, that content – the morphology of moss sporangia, the hydroscopic reflex that launches the spores, the taxonomy of the time - was bread and butter. I didn’t see science as an add-on to literature but part of the world’s fabric to be gathered in to make real the imagined world – that is, science not so much leaked in but out. When I started writing, my prose was spiked with poems, and by the time I’d finished the novel the concision and intensity of poetry had become a daily habit.

*

To write a science poem, one needs an inquisitive frame of mind that draws on both science and poetry. I have an aged BSC in botany and pharmacology, and postgraduate studies in Labour Law and Public Health, that gives me a general grounding in biology, epidemiology and public health, and a bit of law, added to which is the benefit of working in regulatory toxicology to hone and grow my knowledge. A university should make itself redundant, its graduates capable of independently acquiring knowledge. In literature I am an inconsistent autodidact, reading broadly, deeply and systematically, interrogating and questioning the Australian canon, reading across time and place, from Babylonians in the Bronze Age[1] to contemporary Japanese Tanka[2], learning Spanish to read Latin poets such as Jimenez, Benedetti, Vallejo,[3] in their original language, and bobbing between bilingual editions of French and Italian poetry to hear their sonic structures. We learn to write poetry by immersion in its flow, by diligent reading and experimenting with what works. If a poem doesn’t catalyse a reaction for the writer, then it has failed, and must either be revised, abandoned or deleted.

n poetry, I’ve been both my own apprentice, and I’m fortunate to be a member of a workshop group, the Pomegranates, that provides a convivial litmus test for doubtful or tricky poems. Although editing, gleaning and fine tuning is essential, the critical first stage of all my poems is observation, imagination, and analysis. Yesterday I found that the heavy wide-toothed rake sifts the leaves and leaves the gravel much more effectively than its fine-toothed wire partner, and I even as I write this, the idea of separating particles stretches in two directions, one towards metaphor — I think of distillation and elution columns, processes to isolate proteins, the behaviour of large and small particles — and in another direction towards the reciprocities between wide-tooth, fine-tooth rakes as a metaphor for dualities of couples and the synergies of marriage. The rake’s progress, to make a pun, is to comb through one’s mental library. Here, science is a good thing to have on the shelves.

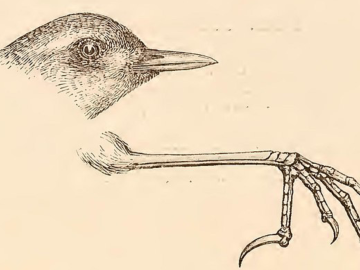

On my physical bookshelves, one of my favourite references books is a classic of taxonomy: Radford’s Vascular Plant Systematics[4]. My copy is a relic from my second year at the University of Adelaide. Even with no academic future in botany I have lugged it around for over three decades for its glorious nomenclature of every plant part. There is nothing quite like having the exact word clearly illustrated. Earlier poems like ‘Pollen’[5] have availed of its precise vocab, and a recent unpublished poem ‘A Transect of North Carolina’ celebrates its gorgeously egalitarian listing of common names, gritty down-to-earth monikers that are descriptive and zesty.

*

The general idea of a scientific paper or study is to pack in as much data as possible in a compressed form, including tables and charts. In a way, any graph is kind of metaphor, as it uses one set of symbolic information -plotted lines, curves and numbers - to graphically present relationships. It is illustrative in the way a figure of speech is: graphically immediate, and also precise. As if to compensate, or offset, for this kind of loading, one of the most significant differences for me between writing for science and writing a poem is the benefit of ambiguity, and the related phenomena of paradox. Many very good poets naturally seek clarity with as much zeal as the science writer, but the difference is the poem welcomes double meaning, inference, and suggestion, and seeks to pack in homophones and cognates. The culturally loaded gauntlet, the literary allusion, can also be thrown in to further enrich the construction, if the odd fly buzzes into your poem, it brings with it, to those who read widely, Emily Dickinson’s fly that is the harbinger of death. Poetry excels at linguistical hijinks and pluralities, while the science report aims for a single meaning.

To me, a date suggests a ratio or an equation. Standing on the deck of my studio I read Geoffrey Lehman’s poem ‘The Golden Wall’[6], and pause to study the two sets of expanding and contracting concentric circles in the garden fountain, one radiating out from the bubbling centre, the other coming inwards from the waves’ reflection from the edge. I think Ahh there is metaphor in need of a poem, this elucidates something, but its poetic destination as yet eludes me. All this reminds me that I am not a static object but a creature of processes, with the thinking process being the most critical ; not to think through what one sees is to be in inadequately alive, or in part, dead. This process of cogitation has been described by Mark Doty[7] as ‘a perceptual signature: — a record of an individual way of seeing’. The description of two sets of radiant circles and their neat collision/collusions might be fine in and of itself, but how this might be built on is a delicious test, a mental game of both pounce and contemplation, often best left to the automatic processes of the unselfconscious self.

Some science poems lurk, while others are of the eureka variation and seem to flow out of the pen, or bounce up under my fingers on the keyboard. But the instant of genesis is always about perception, the data, the senses, and the rigour of knowledge and experience. So the mind has effectively two states of perception: one radiating from an external observation meets with the application of an interior inwardly process of comparison with experience, knowledge and illumination, and these, like the doubling circles in the fountain, join seamlessly to appear as one thing. To look at this from a different angle, say in cross-section being at once containing and overflowing – to rephrase William Blake[8], the cistern contains, the fountain overflows — the fountain/poem needs its reservoir — and the poem must overflow.

*

It might be of interest here to take a closer look at the impetus for the two poems in this issue of ScienceWriteNow. ‘Aprazolam’ turns, in part, on the first-hand observation that while there is no a priori nutritional wisdom in liking the bitter taste of this diazepam-group tablet, the speaker comes to associate its desired effects with the taste, it starts to taste good. The poem is also a short description of anxiety, sympathetic but ironic, because everything really should have a kicker of self-deprecating humour.

‘Sunday on Venus’ complicates and amplifies the relativities of the perception of time. The impetus for this came from a weekly astronomical science newsletter Fraser Cain’s The Universe Today,[9] which is round up of astronomical titbits. It arrives on Sunday, so in part the poem is a rethink of my Sunday as if it would have been on Venus, echoing the banality of Covid-19’s very small domestic orbit, and also a commentary on how we age and routine recalibrates our perception of time.

As the Japanese proverb has it, everything looks like a nail if you are a hammer, and if you are a science-type of poet, many things will yield up a science type of poem. Each event has its own science, falling in love is a cascade of hormones bolstered by social mores[10], getting dumped feels catastrophic but hedonic adaptation means the dumper soon looks less desirable. I get a text message from Red Cross to say thanks, my donation of 500mL of A-Positive is on its way to Nepean Hospital, and I’m reminded of On a Backwater eBay in Seyferts Galaxy[11] – a poem I wrote about blood and climate change, which makes me wonder, fancifully, if my blood-born poetic signature will find some sanguine expression in its recipient?

[1] World Poetry, An Anthology of Verse from Antiquity to our Time, Eds. Katherine Washburn and John S Major, Norton 1998. USA

[2] Modern Japanese Tanka, Ed. Makato Euda, Colombia University Press, 1996 USA

[3] FSG Book of Twentieth Century Latin American Poets, Editor Ilan Stavans, Farrer Straus and Giroux, 2012 New York.

[4] Vascular Plant Systematics is out of print but wonderfully can be found online as a PDF.

[5] ‘Pollen’, page 49, Fishing in the Devonian, Carol Jenkins, Puncher and Wattmann, Glebe, 2008

[6] Page 50, A Quark for Master Mark, 101 Poems About Science, eds. Maurice Riordan and Jon Turney, Faber & Faber, London, 2000

[7] Mark Doty, The Art of Description: World into Word, Grey Wolf Press, 2010, USA

[8] From ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, William Blake.

[9] https://www.universetoday.com

[10] ‘Disorder of Belief’, from Fishing in the Devonian Carol Jenkins, 2008, Puncher and Wattman, NSW

[11] From Fishing in the Devonian.

Feature image via 'Art Collection - The Metropolitan Museum of Art'