The Teak Bed That Led Four Humans to Travel from Singapore to Muna Island, Southeast Sulawesi, and Back Again

Lucy Davis

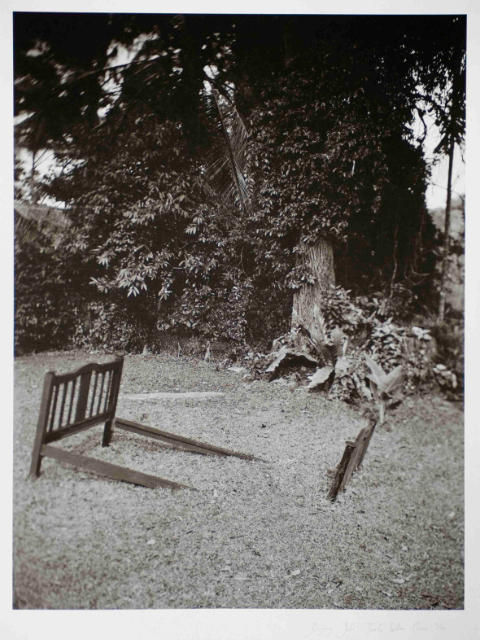

Is it possible to trace the geographic origin of the wood from an old teak bed using DNA-tracking technology typically applied to determine whether timber comes from legal or illegal logging sites in Southeast Asia? This was the question inspiring the artist Lucy Davis and her interdisciplinary collective, The Migrant Ecologies Project, when she found an old bed frame in a junk store in Singapore’s Little India. In an exploration undertaken in collaboration with photographer Shannon Castleman, the bed thus became the starting point for a tracing of the multiple cultural and economic meanings of teak in the Malay region. While it proved to be especially dificult to make any certain claims about which precise forest area the teak wood originally came from, the journeys that unfolded as part of the search opened up a field of forest-culture connections, some of which are unfolded in the following pages. A related series of black-and-white photographs Castleman also produced during these journeys is published in the fourth volume of the intercalations: paginated exhibition series (ed. by A.-S. Springer and E. Turpin), which the Teak Bed essay was originally created for, see The Word for World is Still Forest (Berlin: K. Verlag and Haus der Kulturen der Welt, 2017), 86–95.

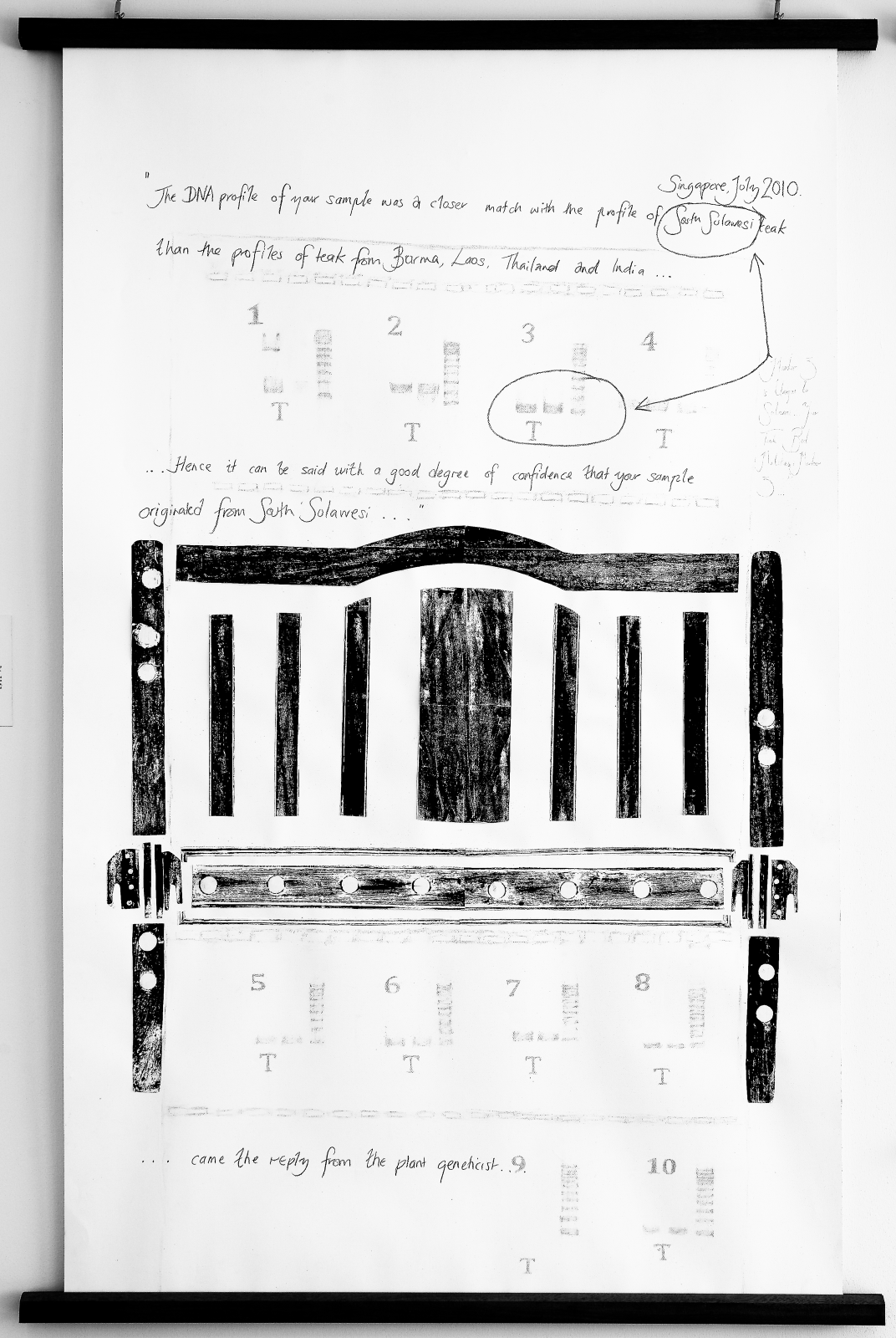

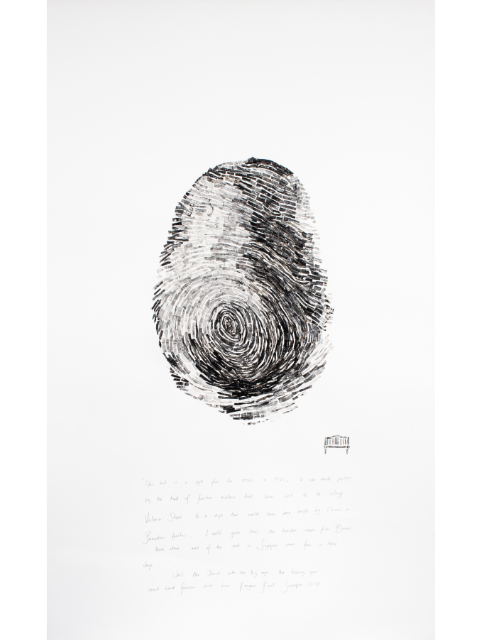

Due to its durability, structure, and natural water-resistance, teak has been used for centuries to manufacture carpentry products, including boats, furniture, and interior and exterior architectural elements. Endemic to South Asi —and possibly some areas in Southeast Asia—the wood became an especially popular export in the twentieth century, leading to the expansion of mono-crop teak plantations and increased deforestation due to selective logging in the region. Like any other living organism, each tree can be identified by its unique DNA signature, also called its “fingerprint.” The Singapore-based start-up Double Helix Tracking Technologies uses their DNA-fingerprinting technology to certify the legality of timber by determining lumber’s site of origin.

In our exploration, the Migrant Ecologies Project collaborated with Double Helix to determine the origin of the second-hand teak bed. Preliminary tests suggested a possible connection between DNA from the bed and teak in southeast Sulawesi [formerly called Celebes]. This insight was based on a theory that teak, cultivated and logged in Indonesia for centuries, had “naturalized” in southeast Sulawesi and that this process might be evident in its genetic structure.

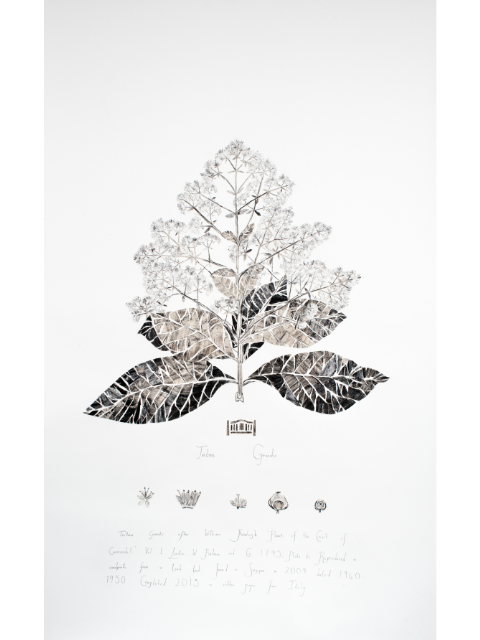

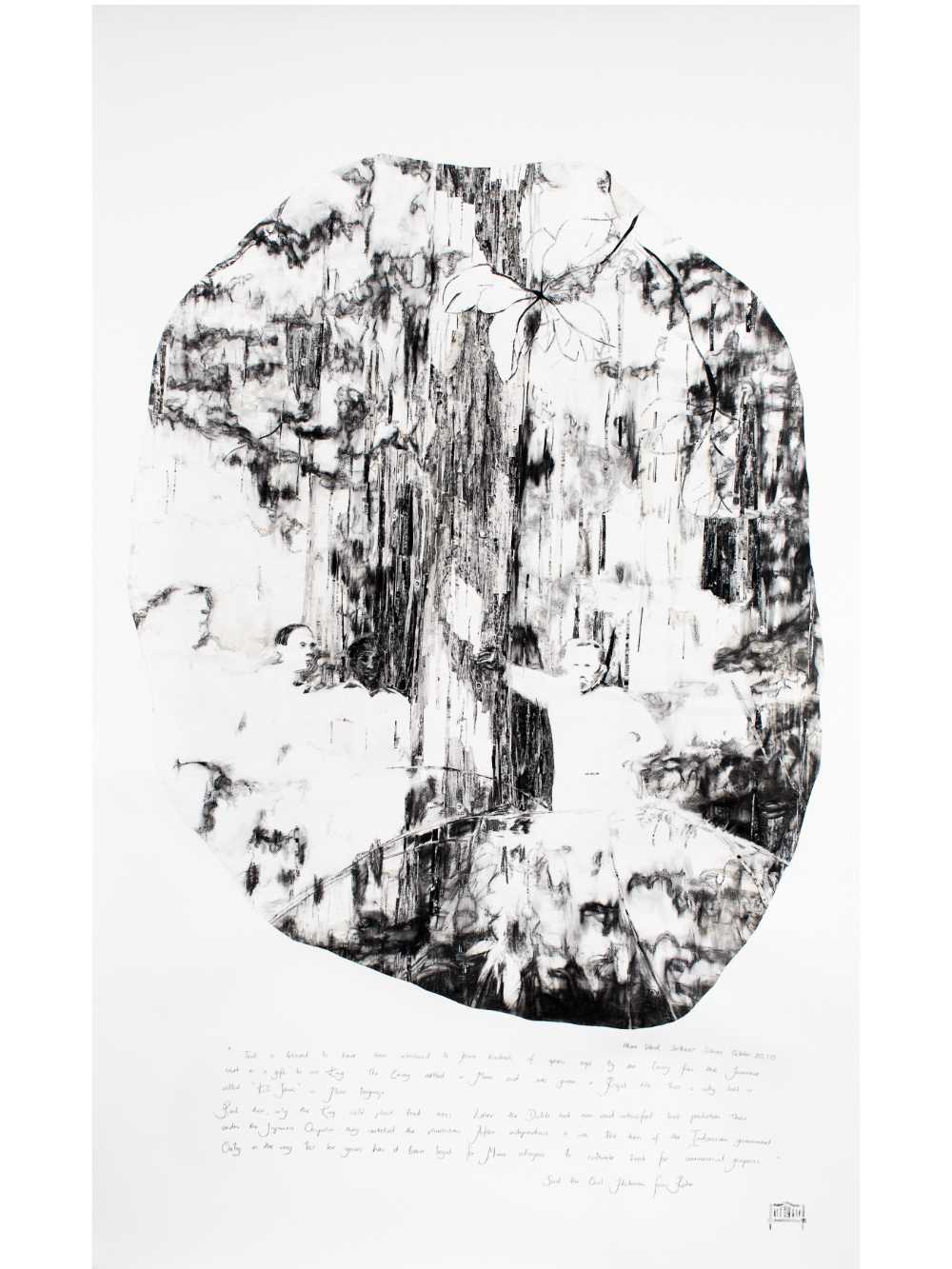

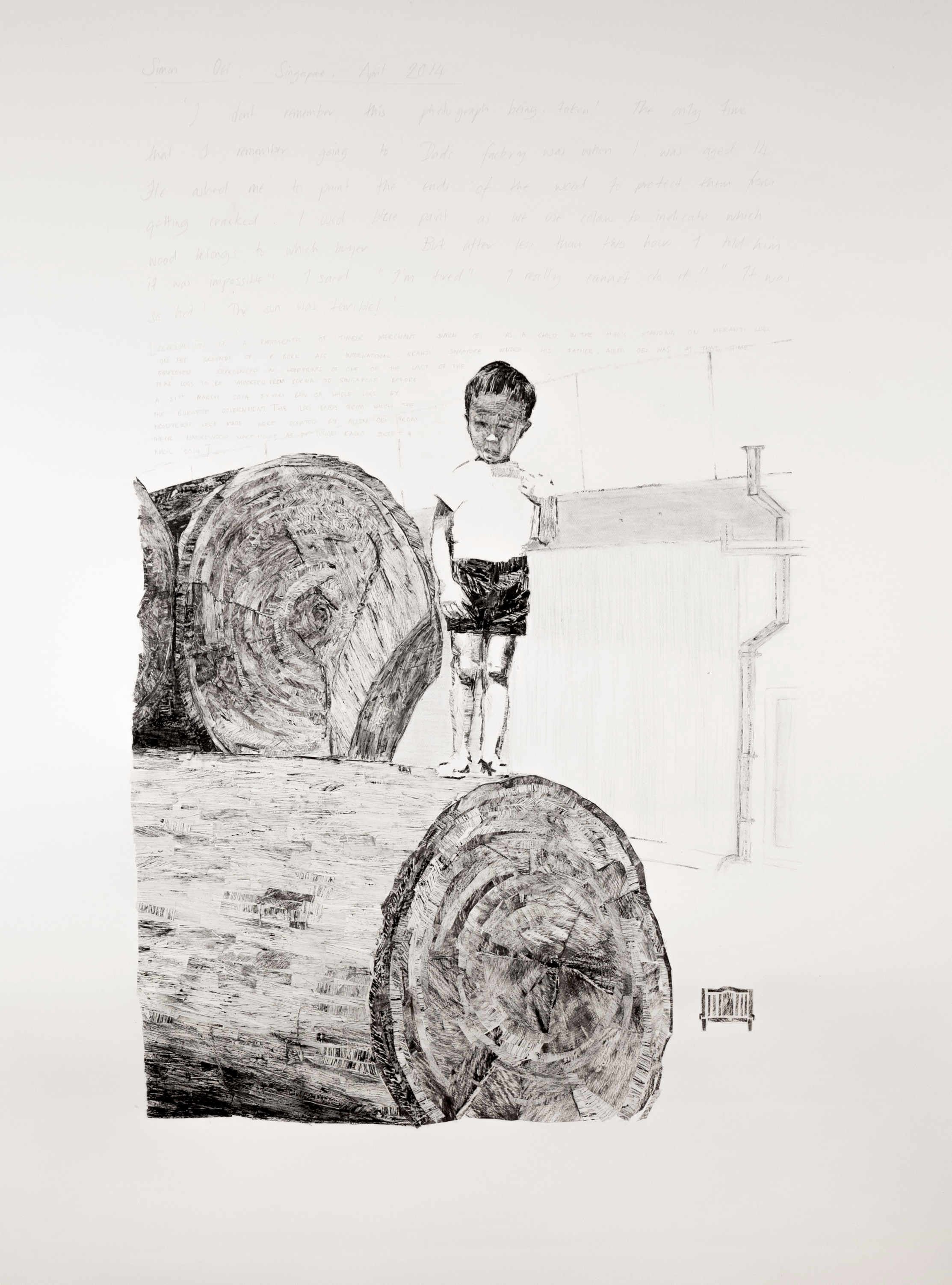

A parallel, art-historical inquiry concerned our fascination with the mid-twentieth-century Malayan “modern” woodcut; we were interested in working with the microgestures of woodcut styles to describe the contemporary macro-ecological context of regional deforestation. As a result, most of the woodprint works that emerged from this five-year investigation were compiled of prints made with the teak bed’s wood.

Before visiting Muna Island, we didn’t entirely grasp teak’s historical impact on land use, which produced environmental and social transformations similar to those unleashed by contemporary oil palm plantations in Malaysia and Indonesia. According to Dr. La Ode Sirad Imbo, a local historian and philologist from Muna, teak originates from Burma, India, and Laos, but was introduced to the island more than 500 years ago. Legend has it that teak seeds were gifts from Javanese royalty to the King of Muna. Initially, only the King could plant teak, with severe penalties for those caught smuggling seeds. Later, intensive cultivation was the purview of the Dutch, who carried out most of the large-scale deforestation in the area. After Indonesian Independence in 1945, plantations were controlled by the Indonesian state.

We heard a saying on the island: “Politik Muna adalah politik kayu” [Muna politics is a politics of wood]. Today, virtually no original forest remains. The decades from the 1950s to the 1990s were timber boom years where demand exceeded supply and sawmills lined the harbor of the main town, Raha. Today, although these sawmills are still standing, they are overgrown with weeds because there is no timber left to sell and forest destruction has significantly affected the water table, diminishing the available freshwater.

Alongside these stories of macroecological change, we were committed to drawing out various related micro-gestures. Things got complicated. While subsistence farms produce food for local consumption and fishing occurs along the coast, the mainstay of Muna’s economy is still teak. Due to regulations on logging meant to curb overconsumption, this meant that until the early 2000s, if one were to survive on a teak economy, one had to do things that were “illegal”—at least according to the discourse of DNA certification. For this reason villagers would for instance make it their practice to cut more teak than they needed for themselves and built houses with double walls, as well as keeping extra stock underneath their homes for “repairs.” After the fall of President Soeharto in 1997, villagers were eventually permitted to plant their own trees. But, because teak trees can only be harvested after twenty or thirty years, many trees in these smallholder plantations for a long time have remained too young to harvest. Instead, illegal logging of recently established konservasi forests—plantations awarded “conservation” status in order to protect groundwater—became widespread. Indeed, as explained below, the only konservasi forests left untouched by woodcutters are those they believe are haunted.

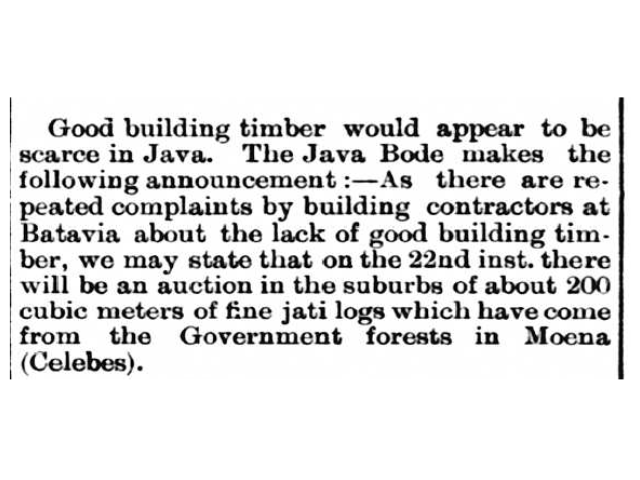

![A reprint of an alert originally published in the Batavian Java-Bode [Java Herald]; clipping, The Straits Times, 29 June 1911.](https://sciencewritenow.com/media/pages/read/migration/the-teak-bed-that-led-four-humans-to-travel-from-singapore-to-muna-island-southeast-sulawesi-and-back-again/f9c6e56a6b-1699247734/fig.-08.-a-reprint-of-an-alert-originallypublished-in-the-batavian-java-bode-java-herald-clipping-the-straits-times-29-june-1911.jpg)

Tales from Two Islands:After a Timber Boom

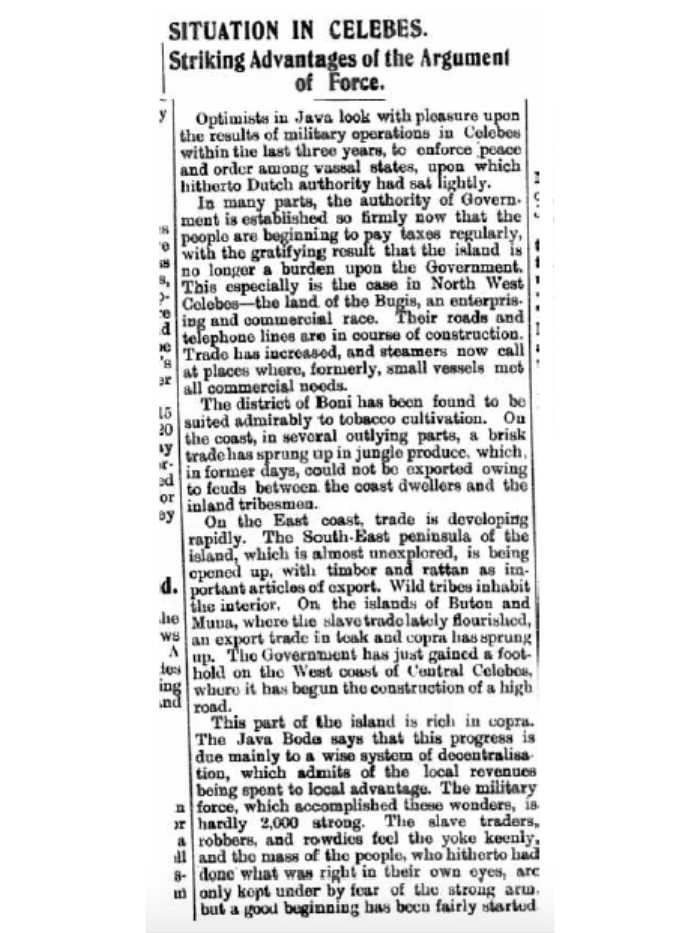

In the early twentieth century, the Dutch are known to have used slavery and suchlike as excuses to move in and monopolize the resources of various parts of the archipelago. Both Sulawesi and Muna produced very “ine jati logs” [Fig. 07.] and other riches, which are often entwined with stories of slave raids on the islands and rebellions on the mainland. During these events, The Straits Times of Singapore sometimes seemed supportive of Dutch efforts to end slavery, improving island folks’ living conditions. [Fig. 09.] But other times the same newspaper would also voice its support for the efforts of the Dutch to intensify their colonial control. [Fig. 08.]

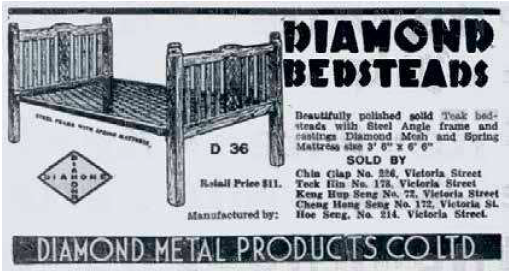

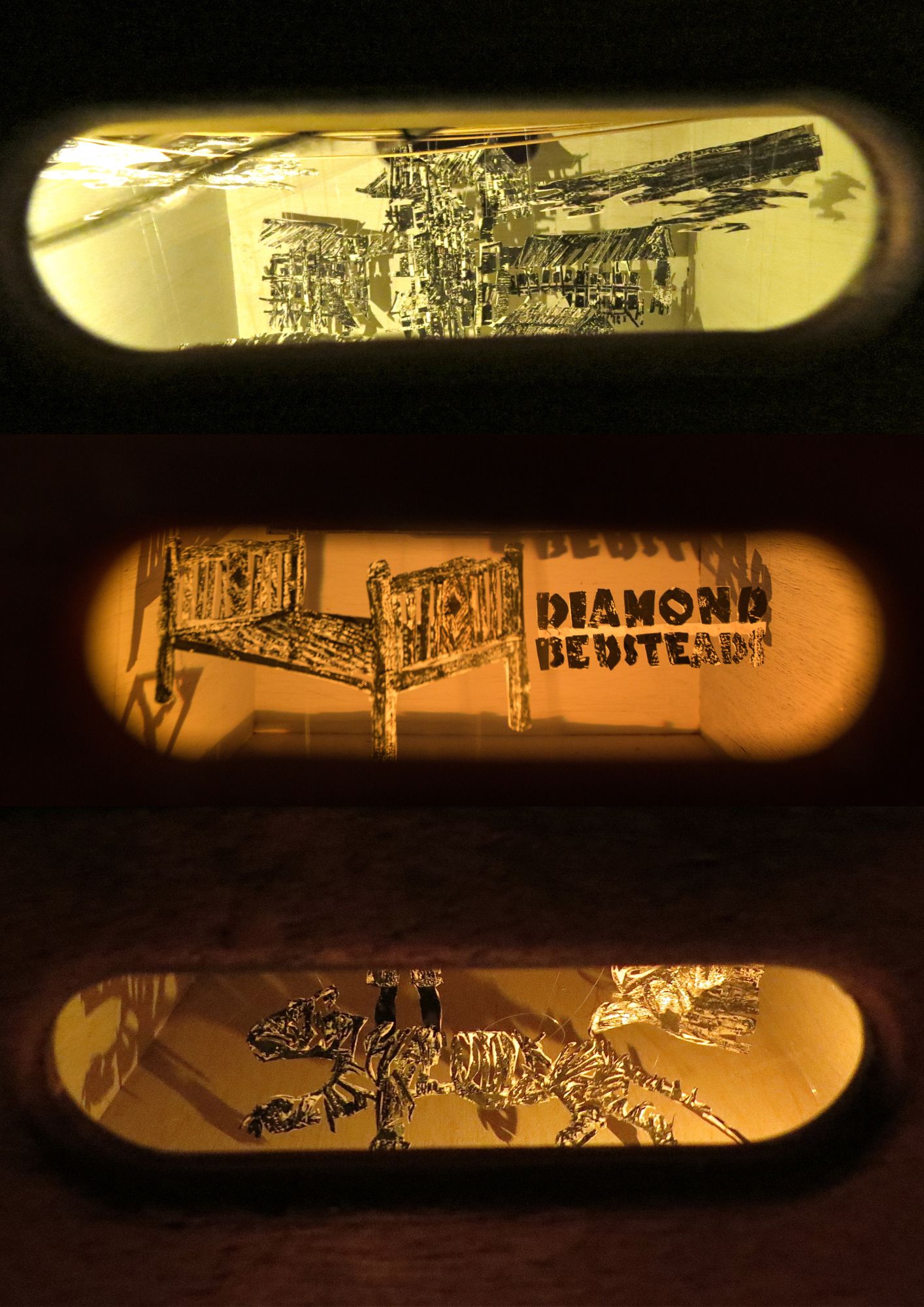

A search through the Singapore National Library’s online newspaper archive turned up an advertisement from 1937 of the very bed’s model found in the store on Rangoon Road in 2009. Diamond Metal was a company set up by long-term local rubber traders Francis Graham and Vernon B. Jepson in February 1927. They produced bedsteads, trunks, and batteries. The teak wood in the advertisement is somewhat incidental as the actual purpose of the ad was to promote the innovative use of metal for the bedstead’s central part. However, it is quite certain that our bed was indeed the same model shown in the photograph, as a careful examination revealed the same diamond formation of the timber on the centerboard. [Fig. 12.]

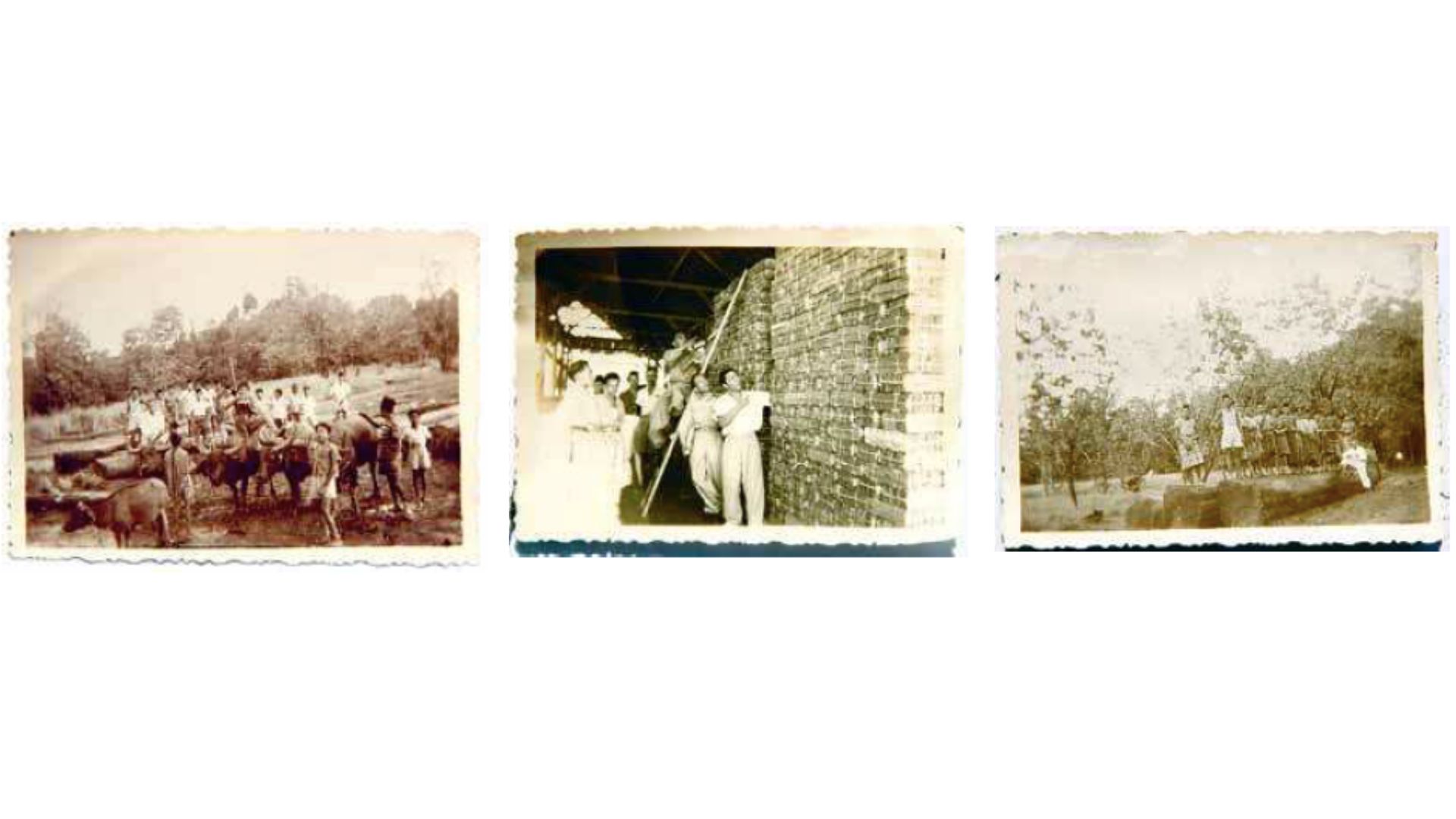

The timber boom continued through the 1970s and 1980s. [Figs. 10–11.] “During those days, everybody worked in the teak plantations. We used buffalo to drag the teak logs. Later there were lorries and cranes with caterpillar wheels. So we sold all our buffalo to traders from Toraja. There are very few buffalo left on Muna now. During those busiest years even the rivers were thick with teak logs. You could walk on wood all the way to the sea,” the head of the Muna village Pentiro told us in 2010. [Figs. 13–15.]

Divining Wood: Magic and Science, Banyan and Teak

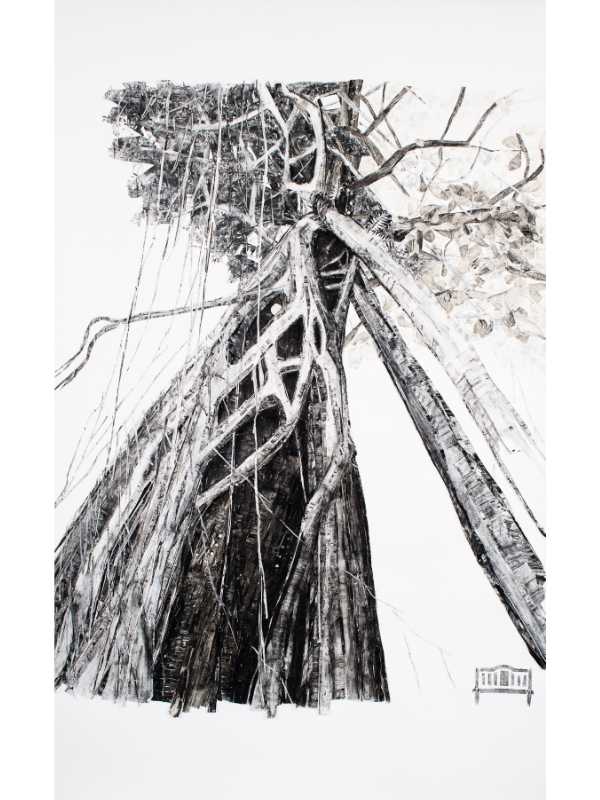

Upon our arrival, the only konservasi plantations left standing on Muna were those considered to be inhabited by spirits. In these hutan-hantu [haunted forests], strange battles ensue between remaining teak trees and the banyan, or strangler’s fig, a parasitic vine. The banyan seed is in most instances dispersed in the canopy by a bird or a bat. The plant puts out aerial roots which, upon reaching the ground enforce a complex cage-like architecture that suffocates the host tree. Residents throughout the archipelago consider the banyan to have potent powers, possibly due to the imposing way it “possesses” other trees.

The ability to divine whether a tree or piece of wood has spirits is the purview of dukun-dukun, traditional arborealists or wood-spirit shamans. A dukun is consulted on matters of healing and fortune-telling. They traditionally advise whether a tree should be chopped down and which kind of wood has to be used in house construction, providing incantations for the process. In Muna architecture—as in many places in Southeast Asia—the root end of a plank must point to the ground and the crown to the sky. For overhead beams, the crown should point towards Mecca. The dukun-dukun claim to be able to discern crown or root ends of a piece of wood just by holding the timber.

We presented the bed to two dukundukun and asked for their interpretation. [Figs. 18–19.] The male dukun responded that our teak was jati-hitam [black teak] of the lowest grade used only for the lavatory and back areas of houses. The female dukun was not as convinced by the DNA reading and claimed that the wood was not from the Sulawesi region.

During these interviews, we met with some resistance from our two Indonesian collaborators—the country manager of Double Helix Tracking Technology and the engineer from the provincial capital of Sulawesi Tenggara, Kendari, who was our fixer and guide. Both dismissed the claims as animist magic and declared their own Islamic and Catholic faiths to be more modern and scientific. However, an interesting discussion developed after I showed them an earlier animation I had made of Alfred Russel Wallace on my laptop and explained how Wallace had formulated a theory of natural selection independently of Charles Darwin. Although they were not familiar with Wallace, the mention of Darwin sparked a negative response; both pronounced that they did not believe in evolution. They did, however, believe in DNA.

Patriarchal Imprints

Two woodprint collages. The first is a reconstruction of an undated photograph of the late Alex Bermuli, a Muna sawmill owner, in a plantation with a group of men around a tree, upon which he has placed his hand. [Fig. 20.] The second one reconstructs a photograph of Simon Oei of Nature Wood Pte Ltd, Singapore, at around four years old. His father, Allen, a timber merchant, had placed him on top of a huge meranti log in the Danish-run timber yard where he worked in the 1970s. [Fig. 21.]

While contemplating the first image, Walter. T. Bermuli told us his father Alex had migrated to Muna in the 1950s. Walter, himself a retired sawmill engineer, allowed us to re-photograph his collection of snapshots dating from the 1930s. [Fig. 13–15.] The men in Walter’s family had all worked with teak for three generations. His son is now a forest policeman.

Like Walter Bermuli, Allen Oei—whose family migrated to Singapore from the Javanese city of Surabaya before the Second World War—gave us access to his photo album during a surprisingly frank series of interviews detailing his rags-to-riches journey from itinerant timber grader to influential merchant. Oei recounted how, in the 1970s, when local authorities discovered his Indonesian colleague logging illegally in Riau forests for a French company, the colleague burned down the entire forest area to cover their tracks. Oei had also been to Muna and confirmed that Muna teak was superior to any other type found outside of Burma.

Allen Oei, by his son’s own reckoning, controlled a significant proportion of the legal and illegal teak trade passing through Singapore in the 1980s and 1990s. But Simon did not recall this childhood photograph being taken. As a young man, he was repulsed by the sweaty, dirty, gangster-like world of the sawmill. He studied computer science at university and worked for a series of multinationals before joining his father’s business at the age of twenty-eight. When we interviewed him in 2014, he was poised to take over Nature Wood under his father’s watchful eye, aware of the ecological complexities of his position yet trying to find ways to defend it. “A timber plantation is, of course, an excellent way to contain carbon,” he asserted.

Allen Oei also donated some logs to the Migrant Ecologies Project. [Fig. 22.] These were supposedly among the last shipment of teak logs that were shipped from Burma to Singapore before the Burmese government enforced a ban on the export of whole logs on 31 March 2014. Letter and number marks were punched into the wood in Burma. They bear information about the grade of the timber and the precise origin of the logs; a star apparently means best quality.

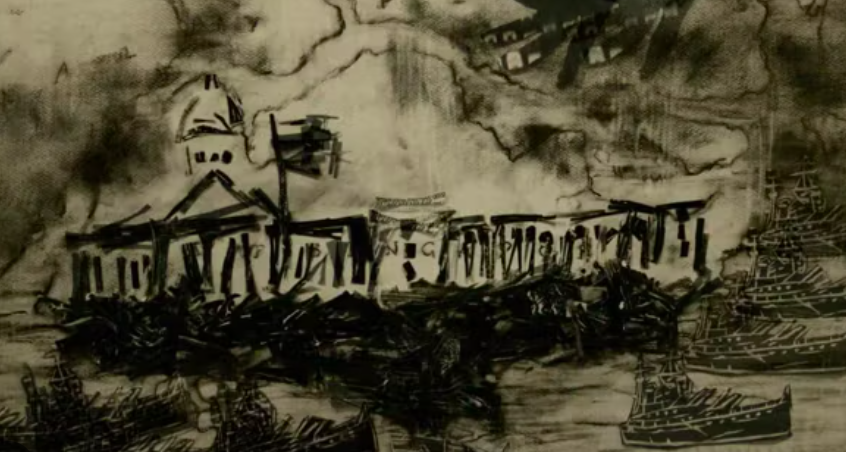

In addition to the aim of retracing a historical wood object to its forest of origin, another aspect of our project was to rethink the legacies of the modern Malayan woodcut printing movement in the context of contemporary deforestation in Southeast Asia. The display architecture of a roomsized installation entitled Nanyang University in our exhibition When You Get Closer to the Heart You May Find Cracks ( National University of Singapore Museum, 2014) thus purposefully echoed a 1955 woodcut print by Malaysian artist Lee Kee Boon depicting the city’s Nanyang University [Fig. 25.] behind traditional balau timber, or mangrove scaffolding. Translating that fragile exoskeleton of a scaffold in Boon’s picture back into three dimensions, wooden archival boxes were placed inside an actual recycled balau scaffolding. [Fig. 24.] This structure evoked the windows of the university building, but also contained shadowpuppet interpretations of other iconic Malayan woodcut works from the mid-twentieth century. Other boxes housed scenes from the 1930s, echoing the period that the original advertisement for our bed in The Straits Times dates back to. [Figs. 12./26. middle] The middle shadow puppets were also made from woodprint collages using either the bed or Allen Oei’s teak logs as seen on the previous pages. In this room of shadow-box dioramas, slowly animated by swinging light pendulums, we intended to conjure layers of half-built, still-breathing dreams of wood where the shadow of the last tiger killed in Singapore in 1937 [Fig. 26. bottom], falls under the bed from the Diamond Bedsteads advertisement of the same year.

Jati-diri and the Naming of Names

This photograph [Fig. 27.] shows assorted wood samples that once belonged to the Botany department of the University of Malaya, later the National University of Singapore. No longer used, this collection was given to the Migrant Ecologies Project by the new Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, which opened in 2015, on the fiftieth anniversary of Singapore’s Independence. The Malay names of the tropical trees are punched into these wood samples: BALAU, BINTANGOR, CHENGAL, JELUTONG, KEMPAS, KERANJI, MELUNAK, MERANTI, PUNAH, and— TEAK. Given the rapid deforestation of the archipelago, one wonders whether and how the Malay names of these trees and their attendant stories will be remembered as these species of trees are becoming ever more rare.

Apparently, there are multiple meanings of the Indonesian word for teak, jati. “Jati-diri” and “sejati” are common: “Diri” means self, while “jati-diri” is often taken to mean identity, personality, or the essence of self. “ Sejati” means pure, true, authentic, original, or genuine. Such translations of jati suggest a layering of our journey—returning via our project to the colonial natural historians and migrant Chinese artists in order to reveal their presence in the archipelago via the adoption of languages, the transcription of forms, and cuttings of wood.

This piece was originally published in intercalations 3—Reverse Hallucinations in the Archipelago, edited by Anna-Sophie Springer and Etienne Turpin, and published by K. Verlag and Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin in 2017. Download the original pdf here.

Image credits:

Fig. 01. Artwork by Lucy Davis. Photograph (by Shannon Castleman) showing the bed frame around the time of the story. Property of National Gallery of Singapore.

Figs. 02–04. Property of National University of Singapore Museum.

Fig. 05. Exhibition view, National University of Singapore Museum, 2014–15. Photos by Lucy Davis.

Fig. 06. Photo courtesy of Shannon Castleman.

Figs. 07–11. Clippings from the Singapore National Library’s online newspaper archive.

Fig. 16. Reproduction courtesy of the artist.

Fig. 17. Property of the National Gallery of Singapore.

Figs. 18–19. Photos courtesy of Shannon Castleman.

Figs. 20–21, 23. Property of National Gallery of Singapore.

Fig. 24. Photo by Norman Ng.

Fig. 25. Reproduction courtesy of the National University of Singapore Museum Collection.

Figs. 26–27. Photos by Norman Ng.